A new playbook for Europe’s capital markets

Plenty has been achieved for financial markets in the EU post-crisis, but today we feel new momentum is needed. We propose a new playbook for turning Europe’s capital markets into a healthier place when the next class of MEPs wraps up their terms.

In a little over a year, EU citizens will vote in the next roster of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). With these elections, the European Commission also gets new political leadership, and we’ll potentially welcome a new Commissioner for financial services, financial stability and the Capital Markets Union (CMU).

A risk in any election year is that projects are left unfinished as fresh faces arrive bearing new agendas. But, in our view, the greater risk in these upcoming elections is sticking to the same well-worn playbook.

Incoming policymakers should focus on three main goals for EU capital markets next year and beyond:

- Create a true single market for financial services,

- Find innovative ways to bring more retail investors into the market, and

- Pursue an evidence-based and proportionate approach to rulemaking that recognises the diversity of market participants.

A lot has been achieved post-crisis for financial markets in the EU. We have increased transparency as a result of MiFID II, implemented important investment product regulations, simplified listing rules and developed a harmonised anti-money laundering rulebook. We’ve also made progress toward a banking union. But too often, competing objectives have stifled progress – especially on CMU.

For instance, while MiFID II brought greater transparency to equity markets, it also introduced complexity and unnecessary restrictions in the trading of some instruments. The same holds true for prudential rules for investment firms. Policymakers set out to create a bespoke regime catering to and promoting a diversity of market participants. Instead we got a one-size-fits-all solution that still largely applies banking rules to investment firms with no banking activities – a situation that should be rectified in the next mandate.

Deeper integration of EU financial services will help deliver benefits and opportunities across the region. EU businesses of all sizes will be able to access a broad range of funding sources beyond traditional bank financing, allowing them to compete on a global scale. A more competitive and integrated single market would also help European citizens embrace investment culture and alleviate a strained pension system.

In that spirit, we offer this playbook for building Europe’s capital markets.

Create a truly single market

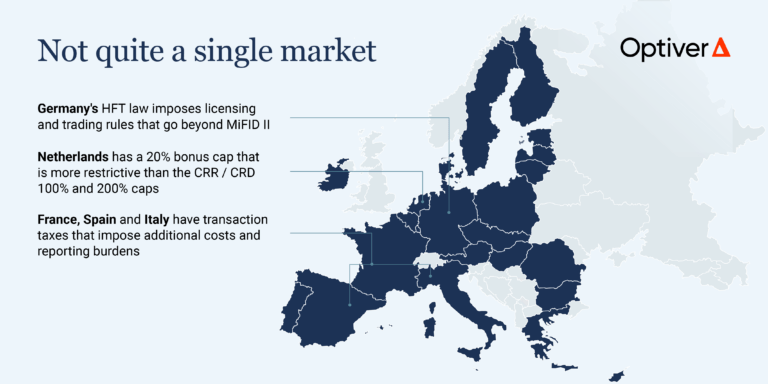

On paper, the EU boasts a single rulebook for financial services. But in practice, each member state implements EU rules in its own way. Member States apply different supervisory standards, set different market access rules, or impose diverging compliance obligations on firms for the same set of EU rules. So in reality what we have is a landscape fragmented into 27 different parts.

Investors and entrepreneurs get understandably frustrated when confronting the diverging tax regimes, insolvency laws and post-trade practices across EU Member States. The map below highlights three examples of national rules that go beyond EU regulatory frameworks (we could have included many more). It’s a single rulebook, but one that lacks harmonised supervision or enforcement.

Empower ESMA

One way to improve this would be to give the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) more teeth. Set up in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, ESMA is a pan-European regulator and supervisor that develops the technical details of how legislation should be implemented or interpreted. ESMA also directly supervises benchmark providers, credit rating agencies and some market data providers. Importantly, ESMA is also tasked with ensuring supervisory convergence among the 27 Member States.

Yet in all (or most) of what it does, ESMA’s decisions are reliant on or approved by national supervisors. Given this, one can legitimately question how effectively it can perform its role. Ultimately, ESMA lacks broad powers to police, enforce and make technical rule changes when needed. ESMA should have an independent mandate that is distinct from national regulators.

We could start by giving ESMA direct oversight over EU trading venues and exclusive exercise of product intervention powers. MiFID resulted in the creation of a large number of pan-European venues, which account for about one third of EU equity trading and remain under national supervision. ESMA could also assume greater powers to impose penalties and sanctions on the entities it oversees. ESMA should have the ability to calibrate technical and implementing criteria for EU primary legislation. And for those concerned with overreach, political checks and balances would be guaranteed with MEPs and Member States needing to approve any changes.

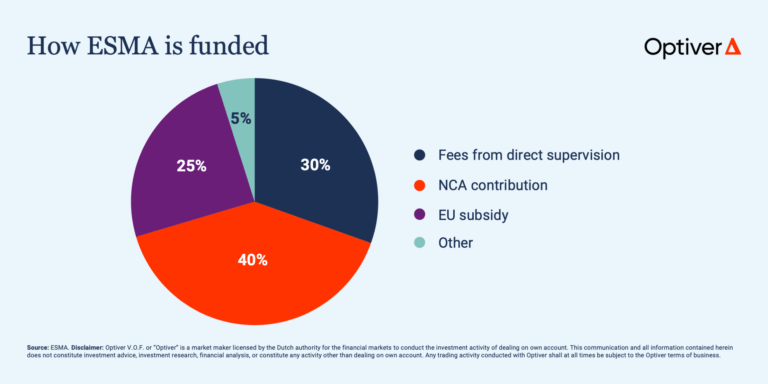

As part of these changes, a rethink of ESMA’s funding is needed. Currently around 40% of ESMA’s funding comes from Member States, a quarter from supervised entities and a quarter from EU balancing subsidy. Let’s allow ESMA to increase the proportion of funding it receives from the entities it supervises.

Taken together, these changes would strengthen the regulator and help make the EU’s financial services framework more nimble and proportionate.

Adopt a true single rulebook

A genuinely integrated capital market requires a single rulebook – full stop. The rules for listing, trading, and post-trade should leave little to no room for national deviation. To achieve this, EU policymakers should to the broadest extent possible make use of regulations as their policy instrument of choice.

For example, organisational requirements for trading venues are currently part of the MiFID directive, which leaves room for individual Member States to interpret them in their own way. By switching these rules to the MiFID regulation, Member States would be unable to deviate from them, allowing firms to operate on a truly pan-EU basis. Greater use of regulations would ensure that rules are applied consistently across the single market – creating a true single rulebook.

Encourage Europe’s retail investors

Boosting participation by retail investors is a win for EU citizens, markets and the economy. It gives individuals access to broader, more competitive investment choices, and contributes to their retirement savings. At the same time, a greater diversity of market participants makes markets more efficient, stable and robust.

Improve data collection

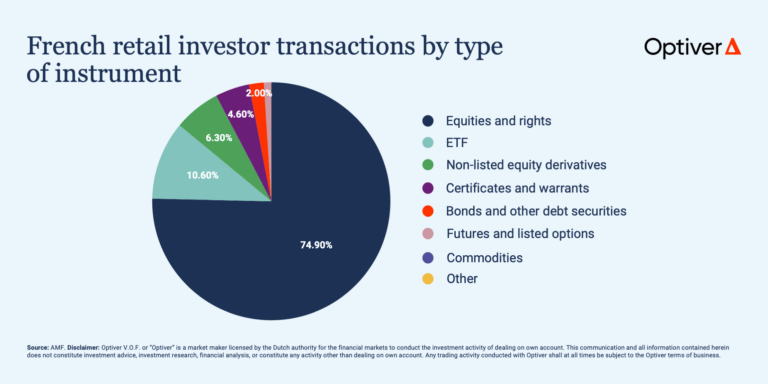

The first step in improving retail involvement is gaining a better understanding of retail investors. As a hotbed of retail investor activity, the world often looks to the US. But Europe has a very different retail culture from the US. US citizens, for example, are more likely to use financial markets to save and invest, while Europeans rely more heavily on banks.

European authorities should do what the French Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) has done in its valuable report Retail Investors and Their Activity Since the Covid Crisis. The French regulator dug deep into the data to produce a compelling portrait of the typical French retail investor. This gives authorities a solid blueprint for engaging with this group. Armed with similar data, regulators could pursue targeted initiatives, like adding basic financial knowledge to school curriculums or encouraging institutions to use social media to promote financial literacy.

Police poor products and practices

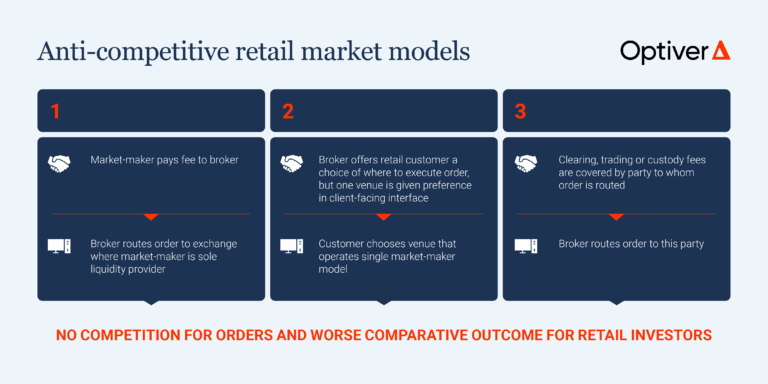

Products and practices that have historically led to poorer outcomes for retail investors should be eliminated or at least be subject to stiffer regulation and disclosure requirements. Studies show that Germany’s single market-maker venues, for instance, lead to worse prices for retail investors. These venues should be reformed so that they are on level footing with multilateral trading venues in other member states.

European regulators have paid an awful lot of attention recently to payment-for-order-flow (PFOF). That’s even though PFOF is less common in Europe than in the US. A PFOF ban may indeed be appropriate for the EU, but regulators should be careful to ensure it’s applied uniformly across Member States. Absent this, a ban could actually lead to poorer outcomes for retail investors and make it more difficult for retail brokers to offer pan-European services. If PFOF is allowed, it should be tightly regulated and accompanied by appropriate disclosures around execution quality.

Finally, structured products, which are more costly, less liquid and transparent, and expose investors to greater counterparty risk than comparable exchange-traded products, should be restricted for retail. Spain is contemplating banning CFDs for retail. That’s the right response in spirit, but EU-wide restrictions would accomplish the same goal, while contributing to a harmonised EU rulebook that’s easier for retail investors to navigate.

Exchanges can also play a role in helping to promote best practices by developing tailored products, such as options contracts with smaller multipliers, and mechanisms that promote on-exchange trading while delivering best execution.

Pursue evidence-based rulemaking

The EU is a sometimes fractious community of 27 Member States, all with competing political interests. As a result, EU rules often end up unwieldy, unnecessarily complex and too one-size-fits-all.

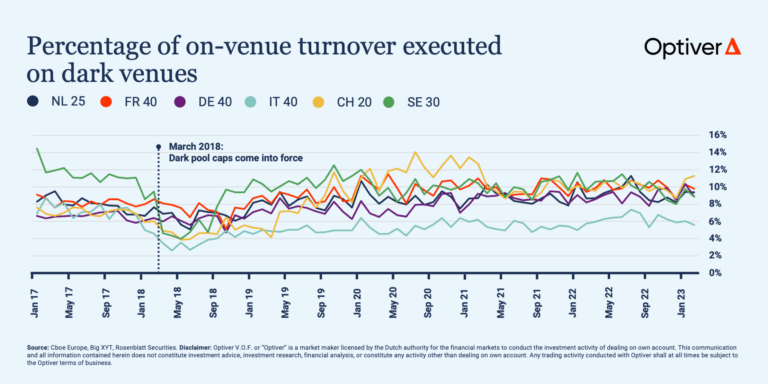

Take the limits on dark-pool trading (also known as the double volume caps). These limits were intended to protect price formation by encouraging more trading on markets where quotes are displayed. When authorities set the caps however – 4% per stock per venue and 8% per stock market-wide – they neglected to conduct an empirical assessment of the level at which non-displayed trading (i.e. trading without transparency on quotes pre-trade) affects price formation on public exchanges. As a result, the volume caps have not had the desired impact. Dark market share has actually increased in some major European stocks, as the chart below shows.

(There is reason for optimism: The European Parliament has recently proposed to empower ESMA to review the volume caps as part of the MiFID review, a measure we hope is retained in the final MiFID text.)

Another example of this one-size-fits-all approach is in the application of banking prudential and supervisory rules. These rules promote market stability and act as a bulwark against the default of large firms. But regulators erred when they decided to apply rules designed for banks to investment firms beyond a certain balance sheet size threshold.

Just as asset diversification lowers the overall risk of an investment portfolio, diverse market participants help reduce systemic risk. Non-bank market makers like Optiver play an important role in providing liquidity and staying in the markets, especially when volatility hits. But treating all firms like they are banks risks undermining the ability of these firms to provide liquidity when they are needed most. Investment firms should be subject to a bespoke prudential regime that is proportionate to their specific risk profile and activities, especially where these firms do not handle client assets or offer any client services.

Policies like these do little to improve our capital markets or encourage trading and investment in the EU. Rulemaking based on empirical data and research means informed decision-making, bespoke rather than prescriptive rules, and transparency that boosts trust and confidence in the financial sector.

All of these objectives together would create a virtuous cycle between regulator and regulated. Focus on these goals and Europe’s capital markets will be in a healthier place when the next class of MEPs wraps up their terms six years from now.

To discuss this paper – or any other market structure topic – reach out to the Optiver Corporate Strategy team at [email protected]

DISCLAIMER: Optiver V.O.F. or “Optiver” is a market maker licensed by the Dutch authority for the financial markets to conduct the investment activity of dealing on own account. This communication and all information contained herein does not constitute investment advice, investment research, financial analysis, or constitute any activity other than dealing on own account.