A guide to how the European Union makes financial laws

It can take years for proposed rules to become law in the European Union. Take the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID). The last consultations for the bill started in 2011, with the final rules entering into force only in 2018.

The EU has plenty more financial rulemaking on its plate, including a review of capital regulations and implementation of cryptocurrency rules. For those wondering what to expect – and when to expect it – here’s our step-by-step guide to how the European Union makes laws.

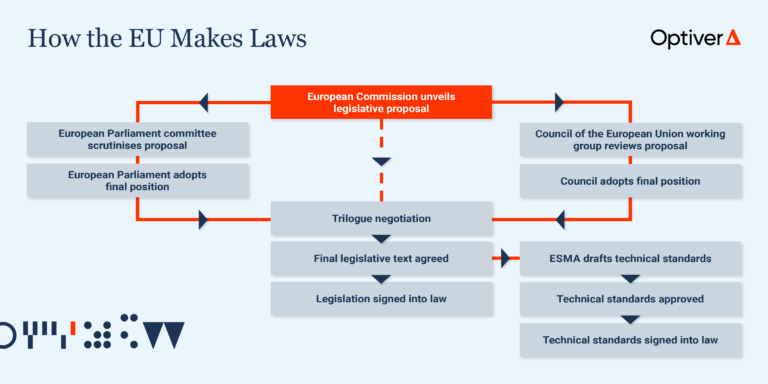

Step 1: European Commission unveils legislative proposal

The European Commission (EC) is responsible for making laws to “defend the interests of the Union and its citizens as a whole.” The EC generally proposes two types of rules: regulations and directives.

-

Regulation:

- Applies to Member States directly and in its entirety.

- Designed to achieve consistency across the EU, which can be particularly important when trying to harmonise certain aspects of market structure.

Example: The Central Securities Depository Regulation sets EU-wide practice for trade settlement to help reduce post-trade complexity for firms trading across the region. Member States must apply it in exactly the same way.

-

Directive:

- Requires Member States to transpose EU rules into national law as they see fit, as long as the overarching objectives are met.

- Effectively gives Member States leeway in how to interpret and implement EU laws.

Example: MiFID started life as a directive in 2007.1 Some MiFID rules, such as those related to payment-for-order-flow are vastly different across Member States. For example, PFOF is permitted in Germany but banned in the Netherlands.

The EC starts with a call-for-evidence, which lays out the legislative options and gives stakeholders their first opportunity to contribute to the debate. It may also conduct an impact assessment that examines economic and other potential effects of the new rules.

Example: The impact assessment for the MiFID review includes details like expected running costs and profits for a consolidated tape of trading data.

Step 2(a): European Parliament scrutinises proposal

The European Parliament (EP) comprises Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) elected in Member States who form standing committees to handle legislative negotiations. The Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee (ECON) handles financial services law. The ECON is currently chaired by Irene Tinagli, an Italian member of the EP’s centre-left Socialists and Democrats group.

For each proposed law, the relevant committee appoints an MEP from one political group to be “rapporteur”. The other political groups appoint shadow rapporteurs that, together with the rapporteur, form the team that negotiates with other EU bodies. The rapporteur presents a draft report with amendments to the EC proposal, before the shadow rapporteurs and other committee members suggest their changes. It then falls to the rapporteur to work out a compromise that has sufficient support from a majority of political groups. For the MiFID review, Poland’s Danuta Hübner, a member of the European People’s Party, is the rapporteur.

Input from practitioners can be particularly valuable when forming policy on complex topics like market structure, so MEPs may seek industry feedback during this stage.

Once a committee agrees a text, the entire EP must approve it by a majority during a plenary session. Once approved, the text forms the EP’s negotiating position, which it takes into the “trilogue” discussions (see Step 3).

Step 2(b): Council of the European Union scrutinises proposal

The Council of the European Union, made up of EU Member State officials, has permanent working groups that meet periodically to debate proposed legislation. The Council often proposes significant changes to draft legislation.

Example: During the 2011 MiFID review negotiations, the Council introduced caps on so-called dark-pools, which are markets that do not publicly display price quotes.

Similar to the EP, Council members may consider industry analysis and have bilateral meetings with stakeholders to help inform their views. After agreeing its position, the working group then seeks approval from the Council’s permanent representatives — essentially Member State ambassadors — before presenting its proposal to EU finance ministers for final approval.

The Council’s legislative amendments must then be approved by 55% of Member State ministers representing 65% of the EU population. If an agreement cannot be reached, the file is sent back to the working group for further revisions.

Step 3: Trilogue

It’s crunch time as the Council and the EP seek to reconcile their individual positions and achieve consensus, with the EC acting as mediator. Trilogue discussions can be politically charged, with each side battling for its interests.

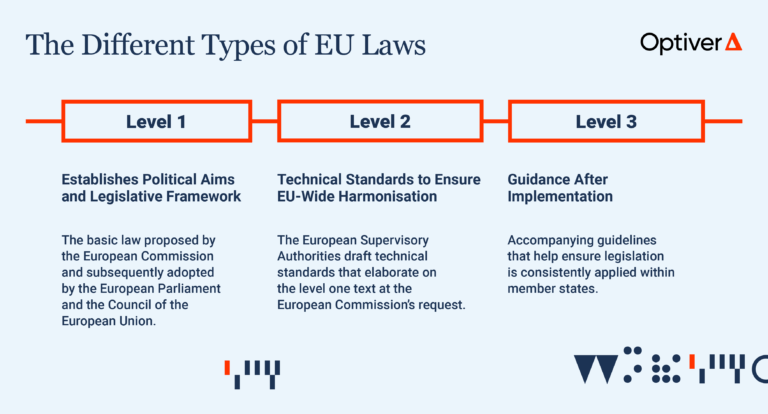

Eventually, a compromise is agreed and a final text is published in the Official Journal of the European Union, at which point it becomes law.2 The core legislative – or level one – text includes a deadline by which the industry must comply. In the case of Directives, it’s a date by which Member States must adopt the statutes in their local rulebooks.

Step 4: Technical Standards and Implementation

For trading and markets legislation, the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) generally develops technical standards that support the level one text prior to implementation. Technical standards provide detailed specifications for how the core regulations should be applied.

Alongside ESMA, the European Banking Authority and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority deal with technical standards in their respective specialties.

ESMA will consult the industry on draft technical standards before submitting them to the EC for approval. The EC will either adopt the standards or send them back for further changes. Once approved, the Council and EP are given a final opportunity to ask ESMA for further changes.

Example: As part of the technical standards for MiFID, ESMA drafted large-in-scale limits, which set block trade size thresholds above which quotes do not need to be published.

In some cases, ESMA will elaborate on or clarify technical standards with additional (“level three”) guidance.

Footnotes

[1] The Commission subsequently added the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation in 2018 to further its objective to create a single EU market.

[2] Some legislation has phased in implementation dates for certain provisions or an overall delayed implementation timeline to allow sufficient time for market participants to adapt.

To discuss this paper – or any other market structure topic – reach out to the Optiver Corporate Strategy team at [email protected]